- Home

- Contact

- Biography

- NCTE/ALAN 2013 Q&As

- Author Visits

-

Crutcher Books

- Other CC Books

- For Educators

- Angus -- The Movie

- Older News Briefs

- Photo Albums

- Scrapbook

- CC Videos

- Student Projects

- Censorship

- Banned Book Videos

- Teens CAN Stop Censors

- Banned Books Week

- Extras!

- CC Press

- Letters to CC

- Movie News

-

Crutcher Speeks

- Update Bantleman/Tjiong

- Nod to Gnuts

- Hip-Hop

- Good Day...

- Gun Referendum

- Free Neil and Ferdi >

- Responsi-damn-bility

- Whacking on Your Children >

- Piling On

- Biopsy Biography

- Walter Elevated Us All

- Different Direction

- Parenting Guidance

- Goodbye, Ned.

- Happy Birthday, Crutch!

- Forrest Bird Charter School

- Senator Portman

- My Gun Rant

- Maybe Now (Guns & Mental Health)

- Support Your Local Pragmatist

- So You Want to Be a Righter

- Philosophy and Humanity

- We Are Paterno

- Boy Scout "Leadership"

- Thoughts on McQueary

- To Meghan Cox Gurdon/WSJ

- India 2011

- Crutcher-Price Blog

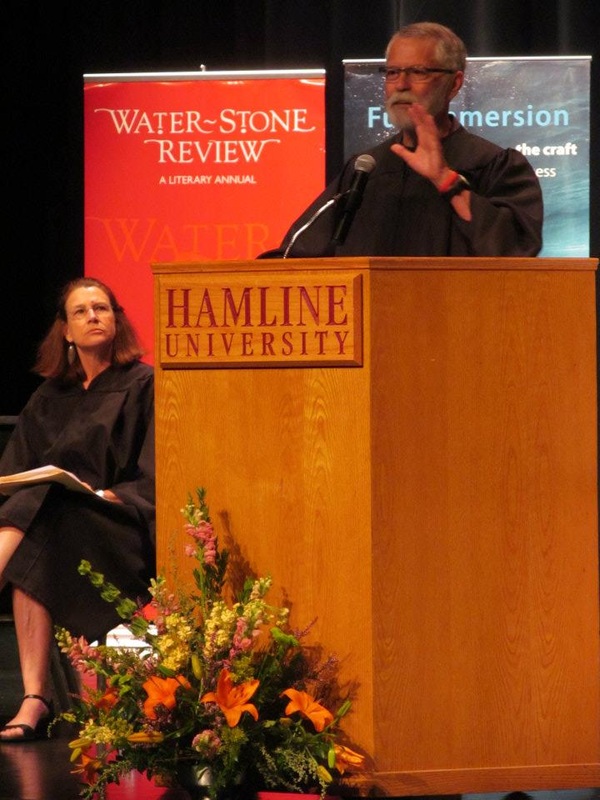

Hamline University's MFA graduation commencement, July 15, 2012.

So You Want to Be a Righter by Chris Crutcher

I told a friend of mine, my partner, that I was giving an address to something that wasn’t a juvenile detention facility, and she said, “Who couldn’t they get?”

I said, “J.K. Rowling, Stephen King, Aiden Stottlemeyer...”

She said, “Who’s Aiden Stottlemeyer?”

I said, “You get my point.”

When I was a young man in my 20’s and 30’s, I went home for Christmas one time and I asked my father what he thought about the idea of me trying to be a writer, and he reminded me that when I write my next book, I would’ve written the same amount of books as I read in high school, so I probably had some research to do. He was a voracious reader, and what he said to me was this, “You know, buddy, all the stories have been told.”

Well that was pretty disturbing information to me. He challenged me to give him a theme or subject, and he would give me at least two novels written on that theme or subject. I couldn’t keep him under four.

As I was turning away with my literary tail between my legs, my father looked at me and said, “But none has yet been told by you,” and it’s all about that perception, that perspective.

I was in Port Townsend in Washington this last week working with some younger writers, and by the way all the authors in Port Townsend knows about this program (Hamline), and they were kind of jealous that I was coming here, and it occurred to me that I was flying halfway across the country to come and ask for you to do one simple thing.

I just want you to save the world.

We’ve tried with war and we’ve broken way more than we’ve fixed. We’ve tried with money and proven ourselves to be greedy liars. We’ve tried with religion and philosophies and we’ve ex’d out more people that we include.

It’s clearer and clearer and clearer to me that if we’re going to do this, if we’re going to save the world, we’re going to do it through imagination.

We have been very short in imagination in the past few decades, and it’s time for people to step up, I think.

I can’t come to a place like this without telling a story, and this story is about my censorship career, it’s the story of my writing career, it’s all tucked into one story.

I was working in a mental health center, and we were working in the world of child abuse and neglect, most of the therapists that came together there. My expertise was supposed to be adolescents and adults, so I worked with a lot of the older kids, and mostly a lot of mean men.

I also worked with a fabulous play therapist, just one of those magical people who can disappear and see the world through the eyes of the child, and we would combine our talents along with a lot of other therapists. We had this wonderful program going, lots of money pouring in, not like today.

We had a lot of money pouring into this program for kids, and it was all about treatment, it was all about getting families back together as quickly as you can because when you break a family up, if there’s any possibility, you gotta get them back together.

Well, we started looking around, and somebody from Head Start called us and said, “We have 17 kids out here, and they’re all in foster care. Why don’t you send some therapists out and we’ll do it all here? We have the parents out already, Head Start brings the parents in to participate, we got the kids, we’ll put them all into one class, send in a couple of therapists and we’ll make this thing dance.”

Well, they brought Carol out, the play therapist, and they brought me out to work with the parents. I’m a little bit nervous because I know adolescents, they’re kinda my thing and all these kids are just in preschool. We’re going out there, and I’m nervous because I don’t know anything about play therapy, I didn’t even know there was play therapy.

Carol said, “Listen, if these kids have been hurt, if they’ve been beat up, it’s statistically a pretty good chance that they’ve been beaten up by men. So just back off and let them come to you. Some will come quicker because they’re tough, and others will wait to see if you’re safe.”

Sounds good to me. Basically what I thought she was saying was that I didn’t have to do anything.

So I went out the first day, and I’d been working down in Oakland, California which is like one of the most diverse places in the universe, and I grew up in Cascade Idaho, a lumber town that is really really white and went to college that was as really white, and after coming back to Washington after working in Oakland I realized I wasn’t in that diverse a place. I walked into the room and there are 17 kids there that are putting their stuff up. Sixteen of them are white, and there’s one little girl who’s mixed race.

Her dad was, well, nobody knew who her dad was because mom wouldn’t tell anybody, but he was an airman, a black airman at the local Air Force base. And mom didn’t, like I said, wouldn’t tell anyone because she knew he would come and save this kid. So she goes off and marries one of the most racist men I’ve ever run into. He was an old carnival worker, and boy the N-word would come out of his mouth like “a, an, the” and he hated this kid. He was on her all the time. There was nothing you could do or say to her but “you’re okay, you’re okay.”

Well, I walk into the building the first day, kids are putting their things up, she’s over there and she’s one of those kids that’s just magnetic. Other kids liked her, you couldn’t see her life on her face anywhere. She walks around, puts her stuff away, then she goes over to the sink. She reaches up and grabs the bar of soap, and reaches up and grabs the brush, and she...

(Chris scrubs his arms in the air)

It’s a stiff brush and it looks like it hurts. I asked Carol what she was doing, and Carol said, “she thinks she can get the color off so her step-dad will love her.”

“Man. Why doesn’t someone tell her he’s a jerk and she’s cool? Let’s get on with this.”

Carol said, “She doesn’t go home with you. When she goes home, she’s going home with him. She’s showing us what her world is like. That’s the way play therapy works. You don’t go telling people everything’s going to be okay. You start where they are. We’ll get to the place where she knows he’s a jerk and she’s a good guy, but we will go on her path.”

Well that makes me pretty nervous.

Then I see her go into the play therapy room. One of the things the play therapists would do each time is take two or three kids who had some kinds of the same trauma of into the play room. The play room’s great, they got every toy you can think of in there; dolls, legos, trucks, cars. You name a toy and we have it.

The little girl, walks into the room, she doesn’t mess with anything she just walks around and picks up dolls. She gets this great big armload of dolls and goes over to this old refrigerator box cut in half and she dumps the dolls in the box. Then she kneels down and she doesn’t look and she reaches in and pulls out a doll. If it’s a light colored doll, she treats it like her little brothers get treated, because mom and stepdad have had two little brothers for her who get everything first. They eat before she eats, they play with toys until they’re broken, she gets leftovers across the board.

It would kill you, because you see this mom when step-dad’s not around, it’s like those two are joined at the heart. But step-dad comes in, mom backs up and this kid is in the eye of the hurricane.

Well, she’s goes into the room and like I said she takes out a light-colored doll and she rocks it and puts it in a cradle and gives it a little toy bottle.

When she takes out one of the darker colored dolls, she treats it like she gets treated. She calls it names, all the filthy names he calls her and kicks it across the room and when she’s finished she leaves it in a heap.

When you watch this play therapist work with her she follows her around. When she’s mad, the play therapist’s mad right with her. When she’is okay and happy because she made some new outcome out of her imagination, the play therapist is happy right with her. But when it’s over she’s left in this little heap and it is really hard to watch.

Well, when I first go in there, I don’t know any of this. I walk into the room and she’s scrubbing on her arm and she sees me. She’s never seen me before. She walks up to me and stands right in front of me like, “Try it.”

I’m not sure what I’m supposed to do so I try to step around her and she steps in front of me. I try to go the other way and she steps in front of me. We do this little dance. I’m not going to get past her. So finally we stand just looking at each other. Finally, she gets this big smile on her face and goes like this:

(Chris raises his arms, like a child wanting to be picked up)

And I dare you not to pick her up, this is the coolest kid in the world. I pick her up, get her at eye level. Her smile gets even bigger, she looks at me and says, “Fucker bitch.”

Whoa.

I heard the therapist say don’t judge, don’t criticize. Well, it sounded pretty funny coming out of a five-year-old, so I laughed. When I laughed, she threw her arms around me and started giggling. I thought, “whoa, this play therapy thing is easy. All you have to do is sit around and say bad words with little kids.”

Well, I was pretty sure that wasn’t true, so I turn to Carol and I said, “Do you know what she just said?”

She just laughed and said, “Yeah, I do know.”

Well, I was worried. I was worried about what would happen when she went to kindergarten, and if she went to kindergarten and talked like that and then she’s out of kindergarten before she knows what’s going on.

Carol said, “Look. This is the smartest kid we have in this room. This kid lives in the eye of a hurricane all the time. Watch any time a new adult comes into this room, especially if it’s a guy. She marches right up to him and runs something up the flagpole. If you’d been angry with her, if you’d pushed her away, you done any of those things you’d be furniture around here. She wouldn’t have anything to do with you. She wouldn’t eat with you, wouldn’t let you read her a book, you’re done. But now you didn’t, and you’ll see her stuff.”

That made sense to me, but I’m still worried about kindergarten.

I remember the year, it was 1985, because it was the year my dad died. And my dad, when he died, willed me his 1979 Lincoln Town Car. Now, I’m driving around in a Volkswagon Bug and this car is the biggest thing you’d ever seen. You could stand across the street and look at this car it touches both parking meters.

I’m afraid to drive this car. But I take it out to Head Start one day because my Bug won’t work, and as I’m driving in one of the foster kids looks at it and says, “That’s a limo.” His foster dad was a limosine driver, so I say no and the kid says, “That’s a limo, and from now on it’s the Head Start limo, and anytime we go on any trips the older kids will ride in the Head Start limo and the other kids can ride in the van, but it’s the Head Start limo.”

Well, I say okay.

Two or three days later we’re going to the humane society, and I take the Head Start limo and it’s perfect. You can take six of the older kids, put them in the back seat, and put one seatbelt over all of them. So I put them in the backseat and we go to the humane society and see the puppies and kittens and things like that, and we drive back into the valley, the kids are back there, I’m driving the car.

They’re kind of bored, they’re messing around, and pretty soon I hear one of them say a bad word. She’s one of the kids back there. Then I hear another kid say a bad word. Then I hear another kid say those two bad words and another bad word. Pretty soon it sounds like the seven dwarves are back there making a porno movie or something.

Well, she’s back there, and she asks, “It’s still okay to cuss in your car, Chris?”

I say, “Yeah, it’s still okay to cuss in my car.”

And she said, “But not when we’re in kindergarten.”

I was like, “What?”

She said, “If you talk like that in kindergarten, no kids will play with you, and they’ll never invite you to their house.”

So she gets the language. I mean, it’s two different languages, it’s the language of messing around in Chris’s car, and it’s also the language of desperation and warning and danger.

We have these kids for a full year, and I walk in the room one day, I look around, and I say wow. 17 kids. 16 kids are going to get to go home. One’s not. There’s no way this guy’s gonna stop calling her names, no way he’ll stop slapping her in the back of the head. We gotta find foster care for her, and it just won’t work.

Some of the best foster homes in the world, we get her out there for five days, six days and she is just golden. She cleans her room, makes her bed, or tries to. She does things no five year old does, or is even supposed to.

But then she starts to get nervous, because every time she’s been in a home before they gave her away. So she does what she did with me, she starts testing it out. She starts the behavior, the foster parents start the discipline. Man, if you’re going to discipline this kid you’d better bring your lunch, she is one tough little girl. And after two weeks, they’re packing her away to sending her back to the social worker.

Three months, six foster homes, and we were running out of time. Her smile is gone.

There was one foster home in town that we knew would work. They were mixed race already so the culture piece is no problem, and these people would run a nail through their eye before they ever gave a kid away unless he was going home. You just didn’t do that. I knew the foster dad, we used to play basketball together, and we’d talk about this kid, he was dying for a shot at her. But we couldn’t get her in, they were always full because they were too good.

I said, “Man, we got to get her in there. I don’t care if it’s midnight, call me.”

One night, it’s not midnight, but it’s about dinner time, the phone rings. He said, “Chris, we just sent a kid home. If you can get her over here tonight we’ll do the paperwork, but if it’s by tomorrow it’s not going to happen.”

I called the play therapist, said, “Go get her, come over and get me, we are going out there.”

Well they come and got me and we’re driving out to the foster home. I’m in the back seat, and she’s riding shotgun. Got her best clothes, little bow in her hair, she just looks gorgeous and she’s sitting like this.

(Chris puts his arms to his side, stiff as a board)

The closer we get to the foster home she starts to rock. By the time we get there she’s so nervous, she’s leaned over and is chewing on the arm rest. Man, it’s a bit of work.

We get out of the car and it’s a big ranch house, sort of a neat shaped ranch house, and it’s dark out and (the house) just looks warm. She gets out the side door and just looks at this house, and I think this is the thing I remember more than anything else that night. She looks at the house and she said, “I don’t know how much longer I can do this.”

Five years old.

These foster parents are unbelievable. We go in and the whole family is waiting, two of their kids and two foster kids, it’s a big place. Well while we were out getting her, Dad was out getting Mcdonalds Happy Meals for everybody. It was just lined up around the kitchen, you walk in there and it’s like the inside of Mcdonalds.

She walks in there and you know she can see the Happy Meals but she doesn’t even pretend like she wants one. She just walks out into the middle of the kitchen, careful not to knock anything over, and just stands there being good. Foster dad is in front of her and is teasing her but she is not getting tricked.

Well he takes out the Happy Meals, pulls out the french fries, and starts handing them to everyone. She takes the bag and start eating one french fry at a time. She’s so careful she’s not even spilling salt. Well, you know what’s going to happen to a five-year-old kid being that careful. They slip out of her hands, hit the floor and they just spill.

She panics. She says, “Give me one more chance, please give me one more chance. I’ll never do that again. I’ll clean that up. I can clean it up.”

I’m over there thinking, “Man, when does this kid get a break?”

But this foster dad is so smart and so quick. He sees her on the floor, he sees her desperation, he sees those eyes, and he just dumps his own fries on the floor. He gets down on his hands and knees and says, “We used to eat them like this all the time! They’re best like this, thank for reminding me!”

She looks at him like he’s an absolute idiot. His two sons are over there and they’re like, “That’s cool.”

(Chris dumps out imaginary fries)

I figure I gotta get in on this too, so I dump my fries. We’re not even picking them up, we are eating off the floor, which is very disgusting, but really funny.

After five or ten minutes, the kids are off in the bedroom playing. We’re getting ready to leave and we’re thinking boy did we just dodge a bullet. I’m on the porch bowing down to these folks, and it occurs to me that I’m probably not going to see her again, because they don’t need us, they’re way better at this than we are. So I run back in to say goodbye and she’s like yeah yeah I got some new friends get out of here. I disappeared, and I got this feeling that we all get, which is I wanted to know what would happen. We never get to know what happens.

Well, I get lucky, because about eleven years later, I get up in the morning to go on a run, and I’m running in a neighborhood I don’t usually go, and I see this high school girl walking down the street. She’s got a band instrument in her hand, and she’s walking down and I think, “That’s her.” I’d know her anyplace.

I start to yell at her and then I think, well, I came out of a pretty ugly time in her life. I probably shouldn’t bring that back up. But she recognizes me and it’s like she saw me yesterday. She was waking up neighbors yelling at me.

So I jog across the street and we’re walking down to the bus stop. She starts telling me about her life, like we were talking about it yesterday.

She said, “I was a devil child. I did everything I could do to get thrown out of that house. I came home one day in the first grade, after I’d been adopted. I was mad at my teacher and my teacher was mad at me. I walked into the house and mom and dad were home but they weren’t looking. “I snuck into the laundry room and smeared poop on the inside of the dryer, turned it on high, and I left.

“My mom came looking for me, and found me hiding in the closet. She picked me up by the shoulders and brought me into the bedroom and sat me down on my bed, and she said, ‘You listen. You belong to us, there is nothing you can do to get thrown out of here, so just stop it.’

“My dad came in and you could tell he thought it was funny because he was biting on his cheeks. He said, ‘Little girl, you can burn this place down but we’re just going to sit here in the ashes, but you’re not going anywhere.’”

She said, “It took me a little while, but I started to feel better. Now I’m a junior, I’m going to get to go to college, I’m getting As and Bs. I did pretty good.”

I said, “I’ve been listening to child abuse stories for 20 years, and yeah. You’re doing pretty good.”

Well, I start to run off, and she says, “Wait a minute! You’ve been writing books.”

I said, “How’d you know that?”

“My teacher made us read one of them.”

“She wouldn’t be a great teacher if she made you read all of them.”

She said, “You know what? If you ever wanted to put my life in a book, you could do it.”

I said, “Well, you’re life’s kind of confidential. I’m a therapist.”

“I’ll sign papers.”

Well, she signed papers.

She said, “When I was a little kid, the worst day every year was the day before school. I’d sit around and think, What if I can’t make any friends? What if I get a teacher like my old step-dad? Think of all the bad things that could happen on the first day of school.

“On the first day, I’d walk into the room, and I’d look around that room, and I knew every kid that had secrets, and they knew me.”

She said, “You don’t tell your secrets. But, if a teacher read you a story, and some of those secrets are in there, it makes you feel like you’re not alone. It makes you feel like she knows you. You can talk about the characters in a book, and you don’t have to tell about your own life.”

And I thought, wow. This kid has just told me what I think storytelling is all about, that connection.

So I did it. I took her story, I had a multi-cultural character telling the story, I thought man if I put this kid in this book it’ll be better than it had any right to be because I don’t have the imagination for this. I stuck with the book and elevated it and it’s called Whale Talk. It elevated because she gave me her story and she said, “Take my life and put it in fiction.”

I get this book banned all the time. Over and over and over. Because when you’ve got a five year old kid yelling out all those bad names, it’s in big font. You go through Whale Talk and read it and go, “Whoa!”

But I go back and I think, “What was she telling me?“

She was telling me if you used your imagination, and you put that story in a book it will connect with a bunch of other kids. And it wasn’t about race. It was about indecency, and it was about finding a way around that indecency. It was about looking at the world through the eyes of the character that you’re telling. It’s about having a good enough imagination, cultivating your imagination, so that you can show a truth.

And the truth has a ring of truth to it. When you get it right, people nod. They go into the story and they stay in the story.

I look around right now, and I think, “Look at what we’ve gotten ourselves into.” Think if we’d been able to talk our leaders into closing their eyes, and putting into their imaginations what that first day of Shock and Awe would be like if you were an Iraqi. Think what might’ve happened if they’d closed their eyes and imagined the horror and the hell the people coming home from that were going to have to live through for the rest of their lives. Think about the officials at Penn State, if they’d closed their eyes and imagined, “that was my kid.” About thirteen years of child abuse wouldn’t have happened.

It’s just too easy to walk away from imagination and come up with some thing that you think you believe in, and call it that and put a talking point on it, and that’s all you have to think about. You can get richer and richer and richer, and even though money is finite, you don’t think about the poor people.

But you can’t turn your back on a good story. You can’t turn your back on a good writer. Some of you are going to write stories for a living and some of you are going to write stories part time. Some of you will write essays, some of you will write poetry that’ll screw people’s insides up. But if we’re going to save this world, we’re going to do it by being smart, and we’re going to do it with imagination.

What I want for you to do right now, is close your eyes, and get to work.

[Transcription by Andrew Steeves -- thanks, Andrew!]

- Home

- Contact

- Biography

- NCTE/ALAN 2013 Q&As

- Author Visits

-

Crutcher Books

- Other CC Books

- For Educators

- Angus -- The Movie

- Older News Briefs

- Photo Albums

- Scrapbook

- CC Videos

- Student Projects

- Censorship

- Banned Book Videos

- Teens CAN Stop Censors

- Banned Books Week

- Extras!

- CC Press

- Letters to CC

- Movie News

-

Crutcher Speeks

- Update Bantleman/Tjiong

- Nod to Gnuts

- Hip-Hop

- Good Day...

- Gun Referendum

- Free Neil and Ferdi >

- Responsi-damn-bility

- Whacking on Your Children >

- Piling On

- Biopsy Biography

- Walter Elevated Us All

- Different Direction

- Parenting Guidance

- Goodbye, Ned.

- Happy Birthday, Crutch!

- Forrest Bird Charter School

- Senator Portman

- My Gun Rant

- Maybe Now (Guns & Mental Health)

- Support Your Local Pragmatist

- So You Want to Be a Righter

- Philosophy and Humanity

- We Are Paterno

- Boy Scout "Leadership"

- Thoughts on McQueary

- To Meghan Cox Gurdon/WSJ

- India 2011

- Crutcher-Price Blog