- Home

- Contact

- Biography

- NCTE/ALAN 2013 Q&As

- Author Visits

-

Crutcher Books

- Other CC Books

- For Educators

- Angus -- The Movie

- Older News Briefs

- Photo Albums

- Scrapbook

- CC Videos

- Student Projects

- Censorship

- Banned Book Videos

- Teens CAN Stop Censors

- Banned Books Week

- Extras!

- CC Press

- Letters to CC

- Movie News

-

Crutcher Speeks

- Update Bantleman/Tjiong

- Nod to Gnuts

- Hip-Hop

- Good Day...

- Gun Referendum

- Free Neil and Ferdi >

- Responsi-damn-bility

- Whacking on Your Children >

- Piling On

- Biopsy Biography

- Walter Elevated Us All

- Different Direction

- Parenting Guidance

- Goodbye, Ned.

- Happy Birthday, Crutch!

- Forrest Bird Charter School

- Senator Portman

- My Gun Rant

- Maybe Now (Guns & Mental Health)

- Support Your Local Pragmatist

- So You Want to Be a Righter

- Philosophy and Humanity

- We Are Paterno

- Boy Scout "Leadership"

- Thoughts on McQueary

- To Meghan Cox Gurdon/WSJ

- India 2011

- Crutcher-Price Blog

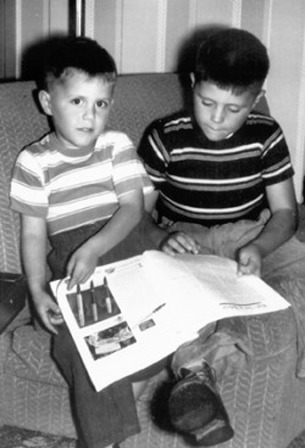

Chris and John Crutcher, olden days.

Chris and John Crutcher, olden days.

Parenting Guidance From the Olden Days

When I was growing up in Idaho, you could get your driver’s license (daylight only) at fourteen. Good reason to stay off Idaho roads in the daytime during the fifties and sixties. No one I knew ever took an actual driving test.

The problem with getting your driver’s license: it gives your parents something to take away when your grades tank or your behavior is less than stellar.

If you drove north out of Boise on highway 15 up into the sticks, the Crutcher lawn was the first you’d encounter just inside the city limit of Cascade, population 943. My mother died three blocks from where she was born, which is to say she was, in my youth, the consummate, even iconic, Cascade citizen. She wanted the folks from “down below,” - who we called “flatlanders” - to be awestruck with our burg and her biggest, best offering was to have our sprawling lawn looking like a freshly mown golf course on Friday evening when weekend vacationers passed through on their way to McCall, the much nicer town that we all hated. She asked my brother John and me to please start mowing the lawn no earlier than Thursday morning and finish before suppertime on Friday.

We promised to comply, then continued to mow small patches whenever we got to it during the week. Our lawn looked like a punk haircut. My mother again stated her request. We agreed, and continued to live our lives as if she had never spoken. My mother didn’t like to get heavy handed, so she continued to make her patient appeal.

My father, who everyone called Crutch, got tired of hearing her ask.

“Boys,” he said one night as we were finishing dinner. “I’m going to lock the mower in the shed each week until Thursday morning. When I come home on Friday evening I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.” His rigs were anything with wheels and an engine.

This was clearly not right. “That’s no fair,” I said. “I work the night shift at your service station. John works days. That means I’m home during way more daylight hours. I’ll end up mowing way more than my half. You gotta come up with something else.”

My dad nodded. “When I come home on Friday evening,” he said, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

Obviously he didn’t hear me. Maybe a little more volume. “That’s not right!” I said. “John will get away with mowing hardly any. It isn’t fair.”

He may have sighed. “When I come home on Friday evening,” he said, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

We’re approaching a meltdown. “You know what he’s like! He’ll trick me! He always does! This isn’t right! What about fairness? What about justice?”

John asked to be excused. Candy, our younger sister, was face down in her plate. My mother stood by the stove shaking her head.

“When I come home on Friday evening,” Crutch said, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

The rage. The tears. The unbelievable unfairness; this final unassailable proof they liked my brother best. If kids had rights my father would be in jail! I’m gonna live with my grandparents.

“When I come home on Friday evening,” Crutch said, probably considering searching his office for my adoption papers, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

Somehow I got through the evening without falling unconscious, swallowing my tongue and being sent for a psych evaluation. By the next morning our interaction was forgotten, or at least not mentioned. For the rest of the summer the lawn got mowed between Thursday morning and Friday at 6:00 and my father never mowed one blade of grass. John mowed half and I mowed half.

“Actually I was fascinated by your obsession with fairness,” my dad said to me at a Christmas get-together probably fifteen years later.

“It sure didn’t carry much weight,” I said.

He laughed. “You didn’t get it. Your mother wanted the lawn looking good for the weekend and I wanted what your mother wanted.”

“Yeah, but…”

He smiled. “Your mother wanted the lawn looking good for the weekend and I wanted what your mother wanted.”

Got it.

-- Chris Crutcher

When I was growing up in Idaho, you could get your driver’s license (daylight only) at fourteen. Good reason to stay off Idaho roads in the daytime during the fifties and sixties. No one I knew ever took an actual driving test.

The problem with getting your driver’s license: it gives your parents something to take away when your grades tank or your behavior is less than stellar.

If you drove north out of Boise on highway 15 up into the sticks, the Crutcher lawn was the first you’d encounter just inside the city limit of Cascade, population 943. My mother died three blocks from where she was born, which is to say she was, in my youth, the consummate, even iconic, Cascade citizen. She wanted the folks from “down below,” - who we called “flatlanders” - to be awestruck with our burg and her biggest, best offering was to have our sprawling lawn looking like a freshly mown golf course on Friday evening when weekend vacationers passed through on their way to McCall, the much nicer town that we all hated. She asked my brother John and me to please start mowing the lawn no earlier than Thursday morning and finish before suppertime on Friday.

We promised to comply, then continued to mow small patches whenever we got to it during the week. Our lawn looked like a punk haircut. My mother again stated her request. We agreed, and continued to live our lives as if she had never spoken. My mother didn’t like to get heavy handed, so she continued to make her patient appeal.

My father, who everyone called Crutch, got tired of hearing her ask.

“Boys,” he said one night as we were finishing dinner. “I’m going to lock the mower in the shed each week until Thursday morning. When I come home on Friday evening I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.” His rigs were anything with wheels and an engine.

This was clearly not right. “That’s no fair,” I said. “I work the night shift at your service station. John works days. That means I’m home during way more daylight hours. I’ll end up mowing way more than my half. You gotta come up with something else.”

My dad nodded. “When I come home on Friday evening,” he said, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

Obviously he didn’t hear me. Maybe a little more volume. “That’s not right!” I said. “John will get away with mowing hardly any. It isn’t fair.”

He may have sighed. “When I come home on Friday evening,” he said, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

We’re approaching a meltdown. “You know what he’s like! He’ll trick me! He always does! This isn’t right! What about fairness? What about justice?”

John asked to be excused. Candy, our younger sister, was face down in her plate. My mother stood by the stove shaking her head.

“When I come home on Friday evening,” Crutch said, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

The rage. The tears. The unbelievable unfairness; this final unassailable proof they liked my brother best. If kids had rights my father would be in jail! I’m gonna live with my grandparents.

“When I come home on Friday evening,” Crutch said, probably considering searching his office for my adoption papers, “I’m going to mow the lawn…if it hasn’t already been mowed. If I mow one blade of grass, nobody uses any of my rigs for the rest of the week.”

Somehow I got through the evening without falling unconscious, swallowing my tongue and being sent for a psych evaluation. By the next morning our interaction was forgotten, or at least not mentioned. For the rest of the summer the lawn got mowed between Thursday morning and Friday at 6:00 and my father never mowed one blade of grass. John mowed half and I mowed half.

“Actually I was fascinated by your obsession with fairness,” my dad said to me at a Christmas get-together probably fifteen years later.

“It sure didn’t carry much weight,” I said.

He laughed. “You didn’t get it. Your mother wanted the lawn looking good for the weekend and I wanted what your mother wanted.”

“Yeah, but…”

He smiled. “Your mother wanted the lawn looking good for the weekend and I wanted what your mother wanted.”

Got it.

-- Chris Crutcher

- Home

- Contact

- Biography

- NCTE/ALAN 2013 Q&As

- Author Visits

-

Crutcher Books

- Other CC Books

- For Educators

- Angus -- The Movie

- Older News Briefs

- Photo Albums

- Scrapbook

- CC Videos

- Student Projects

- Censorship

- Banned Book Videos

- Teens CAN Stop Censors

- Banned Books Week

- Extras!

- CC Press

- Letters to CC

- Movie News

-

Crutcher Speeks

- Update Bantleman/Tjiong

- Nod to Gnuts

- Hip-Hop

- Good Day...

- Gun Referendum

- Free Neil and Ferdi >

- Responsi-damn-bility

- Whacking on Your Children >

- Piling On

- Biopsy Biography

- Walter Elevated Us All

- Different Direction

- Parenting Guidance

- Goodbye, Ned.

- Happy Birthday, Crutch!

- Forrest Bird Charter School

- Senator Portman

- My Gun Rant

- Maybe Now (Guns & Mental Health)

- Support Your Local Pragmatist

- So You Want to Be a Righter

- Philosophy and Humanity

- We Are Paterno

- Boy Scout "Leadership"

- Thoughts on McQueary

- To Meghan Cox Gurdon/WSJ

- India 2011

- Crutcher-Price Blog