- Home

- Contact

- Biography

- NCTE/ALAN 2013 Q&As

- Author Visits

-

Crutcher Books

- Other CC Books

- For Educators

- Angus -- The Movie

- Older News Briefs

- Photo Albums

- Scrapbook

- CC Videos

- Student Projects

- Censorship

- Banned Book Videos

- Teens CAN Stop Censors

- Banned Books Week

- Extras!

- CC Press

- Letters to CC

- Movie News

-

Crutcher Speeks

- Update Bantleman/Tjiong

- Nod to Gnuts

- Hip-Hop

- Good Day...

- Gun Referendum

- Free Neil and Ferdi >

- Responsi-damn-bility

- Whacking on Your Children >

- Piling On

- Biopsy Biography

- Walter Elevated Us All

- Different Direction

- Parenting Guidance

- Goodbye, Ned.

- Happy Birthday, Crutch!

- Forrest Bird Charter School

- Senator Portman

- My Gun Rant

- Maybe Now (Guns & Mental Health)

- Support Your Local Pragmatist

- So You Want to Be a Righter

- Philosophy and Humanity

- We Are Paterno

- Boy Scout "Leadership"

- Thoughts on McQueary

- To Meghan Cox Gurdon/WSJ

- India 2011

- Crutcher-Price Blog

NCTE/ALAN 2013 -- Boston, MA

After his keynote at ALAN in Boston, MA, CC received a list of questions unanswered. Those questions, and his answers are featured below. If you have other questions, contact CC at [email protected] or his assistant at [email protected] and we'll add them to this collection of Q&As.

(PHOTO LEFT -- ALAN Keynote, Boston 2013)

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Q: Why does he write for young adults rather than any other age group? It would be interesting to hear about his writing process.

A: It wouldn’t be interesting to hear about my writing process; it’s diagnosable. It’s pretty much “what if…what if…what if…

I never think I’m writing for young adults. I think I’m writing about young adults. I like that aged character because that time is the first in our lives when we look at the world through what will become adult eyes. It’s an age that is often pooh-poohed by adults. We tend to call adolescent romance “puppy love” and consider teens problems frivolous, but how they handle those problems is the source material for how they’ll handle things as life gets more complicated. Brain science tells us this is a formative time.

Q: Chris, of all the touching characters you have given us, which one was hardest for you to write?

A: Probably Jennifer Lawless from Chinese Handcuffs. Though I had worked with a lot of girls with sexual abuse in their histories, I only knew it from the outside. I couldn’t afford to get it wrong because if I did, the entire book would be invalidated. Luckily two of the girls I was working with were voracious readers who wanted their stories told without actually having their stories told, so they became my editors. When I wrote something into Jennifer’s thoughts or conversation that didn’t ring true, they would let me know in no uncertain terms. Partly she was hard to write because she was so trapped. While I’m writing I’m paying so much attention to the craft that I don’t have much of an emotional response, but when I read it over later, I do.

Q: Do you ever hear the voices of potential censors as you write? Do you listen to what they have to say?

A: Naw, I don’t hear their voices as I write. I barely hear their voices when I’m in the room with them. Truth is, I don’t have much respect because the content of what they say is usually devoid of knowledge of child development or of how connection with characters spurs kids’ creativity. They consider themselves experts in education when most have never taken a class in education or tried to work with a classroom full of students. They project their own fear and discomfort onto students without ever asking students. Listening to their voices as I write would be like pouring superglue over my keyboard.

Q: Given our ever-shifting society, have your assumptions about your intended audience changed over the course of your career?

A: Not really. The “ever-shifting” is pretty much back and forth, so what goes around comes around. I don’t make a lot of assumptions about my intended audience anyway, and in fact don’t consider any one group “intended.” Every smart writer I’ve ever heard will tell you “The story is everything.” I’m more likely to write to one or two good readers who I trust to tell me when the story works and when it doesn’t.

Q: Which comes first as you envision a new story—the protagonist? The conflict? The outcome? Something else?

A: That really depends on the story. Sometimes an event will trigger a story and sometimes a person or persons will. I start with anything that fires me up; spurs my intensity. I would love it if the outcome got me started because I would know in which direction I’m writing from the first page, but that never happens.

Q: What is your most censored YAL book?

A: Whale Talk

Q: Any censorship battles that you lost? Or are still on-going?

A: God yes. Lost a bunch of them. The first one I lost I didn’t even know I was in… at Cascade High School in Cascade, Idaho, where I graduated. Students were required to bring a note from a parent to check out my first book. Nine hundred forty three people total in the town. My mother died three blocks from the house where she was born, so by the time it was published, she was the Grande Dame of Cascade, Idaho. If my mother walked into your house and you didn’t have a copy of Running Loose on your coffee table, woe be unto you. The only building in town where you couldn’t freely pick up a copy of Running Loose was the school.

Lost another battle to the Superintendent of Public Instruction of South Carolina, as near as I know the only Democrat who ever took me out. She was in a life and death political campaign for the U.S Senate against Jim DeMint (sp), that ultra-sensitive conservative SC senator who wanted all homosexual teachers and foster parents to be stripped of their certifications…and that was just the beginning for ol’ Jim. The State Superintendent (Inez Tenenbaum – who now works in the Obama administration) got hijacked by a small, loud group from the Christian Right who wanted Whale Talk and two other books – A Separate Peace and Lay That Trumpet in Our Hands – removed from a voluntary summer reading list. I think she decided she had to give them something, so Whale Talk became the sacrifice. She’d have been better off to go with A Separate Peace, given Knowles is dead. What she didn’t know was that coincidentally I had been invited to the South Carolina Teachers of English conference to deliver the keynote. Many of the members were so articulate in their anger that she took me up on my offer for a sit-down. She was far too ensconced on her position to back out, and we had a pretty uncomfortable discussion that started with me saying “I’ve had this argument a number of times in my life but never with a Democrat.” As far as I know the book still isn’t on that list. There are a number of others I’ve lost.

Q: Who do you write for? Yourself? Troubled teens? Both?

A: I really do write for anyone who might pick up one of my books.

Q: What do the censors find objectionable? The language? The context? Both?

A: It’s my belief it’s more context than language, though language is a more convenient target. I usually start out my part of the language argument saying I never read anything in the Christian Bible about “fuck.” But if I put a gay character in a book who isn’t a freeway sniper or a serial killer, I’m somehow putting gay ideas into kids’ heads that will surely turn into gay behavior. If a character defies authority there is often an accusation that I’m advocating that . Same with a character who has sex out of wedlock, etc. etc. Funny that they don’t complain too much about gunplay.

Q: You write novels that shed light on ‘dark subjects’ – kids do but often, do not tell – Do you think parents have a right to object because you are acting more like a therapist than a novelist?

A: This is the United States of America. Parents have a right to object to anything they want. I’m not sure if the questioner is saying I act more like a therapist than a novelist or if he/she ‘s saying parents think that, but shedding light on ‘dark subjects’ doesn’t mean I’m acting like a therapist. It means I’m taking knowledge I’ve acquired from being a therapist and using it to tell what I consider a truth about my characters’ lives. When it comes to rights, they have the right to complain and characterize me however they want, I have the right to write my stories, and readers have the right to read them. Those parents also have the right to forbid their kids to read my books, and I wish them luck with that, I really do. But they do not have the right to decide what other people’s kids can read and I’m always surprised at those times when they somehow get the right to tell educators how to educate. That is usually the fault of administrators who are more concerned with how the school looks to the community than serving their clients: the students and the teachers.

Q: As America becomes more diverse and inclusive, have you noticed a change in the censorship fights? More? Less? The same?

A: The censorship fights seem to be the same. As America becomes more diverse and inclusive, the censors become more threatened and therefore louder. I’m counting on this diverse population to finally make the censors’ arguments appear as ludicrous as they actually are. I do think this wonderful mix is going to change things. I’m tired of being embarrassed to be a white American male. I really wish I were going to live longer.

Q: Do you meet many arm-chair liberals? Parents who praise your work, but would rather have their kids read ‘Jane Eyre’ and ‘Great Expectations’ because that is what smart kids read?

A: I do, and I usually tell them I think it’s a mistake to do “either-or”. If you give any sharp YA literature expert a theme from any classic, he or she can give you that same theme in contemporary YA literature, and the theme doesn’t have to be explained so thoroughly because it’s in language today’s kids speak. If I struggle through a Shakespeare play, then have it explained to me, even by a great Shakespearian teacher, I miss the intimacy of connection with the character because rather than have the experience of connecting directly to that character while I’m into the story, I get it intellectually. So I may come away with an understanding, but I’m missing the passion of being buried in a good story in real time. There is value in that intellectual pursuit but if you want me to become a life-long reader you want to find a way to my heart as well as my brain. Plus, I can’t tell you the number of AP kids who have told me the best ways to make a teacher think you’ve read a story you haven’t read.

Q: Did you ever have someone get into your face? Directly accuse you of ‘damaging ‘ minds because of your dark and realistic writings..?

A: Yes. I’ve often been called “an agent of the Devil.” About a year ago someone came right out and called me “the Devil.” The actual guy. I thought, “I finally made it. I’m tired of playing second fiddle to that asshole.” So I had a beer. If I’m not being quite so much of a smartass I try to get them to imagine the thought processes I must go through to intentionally damage minds.

Q: Do you self-censor? If not, do you find yourself ‘doubting your choices?’

A: I wouldn’t call it “self censoring”. I don’t censor what I write about, other than I don’t write about things I don’t know about, or don’t feel competent finding out about. If I write something I feel is too graphic in the sense that it takes away from the story I’m trying to tell, I tone it down. What I don’t do is worry about what the so-called censors will think. That said, I am always doubting my choices. I live with the fear that some choice I make doesn’t push the story realistically where I want it to go. That’s one reason I love my editor. Even if we don’t agree we put words to the doubt and I have a better chance of making a right choice.

Q: Have your books become establishment? You are accepted because you are a name and therefore, if it is Crutcher, it must be good?...

A: Boy, if that’s true, I have no evidence of it. I think there are plenty of people who might say “this is a Chris Crutcher book,” or “this doesn’t seem like a Chris Crutcher book,” but I think in general if I write a book that’s not very good, I don’t get a pass.

Q: Working on something new that will raise eyebrows?

A: Am I ever. I’ve recently submitted a book about a character who shows up in a town twelve years after a horrific Christmas mall shooting. The kids who were visiting Santa Clause as first and second graders when it happened are now juniors an seniors in high school and the reverberations have ricocheted through all their school years. Gotta stop there, to avoid spoilers, but the conversations between Jesus and Superman in the main character’s essays alone could stir a little ire. (They’re really funny.)

Q: Chris: I have heard time and time again that if we don't have young adult readers read "the classics" they may never have cause to read them again in their lives. One might make the same argument for young adult literature.

A: One very well might, but in my mind that’s not the point. If you give me “the classics” and I have no emotional response to them, or they’re simply outside my capacity to appreciate, that’s a negative return. If I read a young adult novel that does get a passionate response from me, there’s a pretty good chance I’ll keep looking for stories that do that. Very likely they won’t be young adult literature down the road, but I will keep looking for the stories that draw me in. In other words, YA literature is part of a natural progression. There would be a lot better chance of my reading the “classics” in my later years had I been able to fall in love with stories I related to and then expand from there. We want to keep the idea of “development” in mind. Plus, the discussion about the classics and young adult literature isn’t “either-or.” They are in no way mutually exclusive. There are high school and even middle school students who will eat them up…love them. Those students should be encouraged to the max. They are the ones who will actually keep those classics alive.

Q: Is the introduction to young adult literature just as important as the introduction of classics in the secondary English classroom?

A: Yes.

Q: I think I'd like to know if he thinks his audience has changed much over the years. We always hear the statement, "Kids today..." followed by some big thing kids did or didn't do 20 years ago, but does he feel the teens he writes for now are very different from the teens he wrote for when he began writing?

A: Times change quickly. Evolution doesn’t. If the teenage Chris Crutcher weren’t far more like the teenagers of today than different, I wouldn’t be able to write about them. That “Back when I was a boy/girl” thing is a function of memory and perception. Things happen faster now. Information is more available. Competition for certain things has gotten ridiculous. But brain development and emotional/psychological development hasn’t changed.

Q: And, I'd love to know what other YA authors he enjoys as a reader.

A: Wow. On a given day probably a bunch of different answers. My problem answering is the number of far-better-writers-than-I that I would leave out.

Q: During your writing career, you've tackled many controversial topics and issues. Are there any topics that you avoid? If so, what are they? What makes you shun them?

A: There aren’t any I’d avoid that I know about. The only things that make me avoid a topic are ignorance or lack of interest.

Q: Why do your books seem to provoke so much controversy?

A: I think the biggest reason is a certain level of irreverence toward institutional thought. I have what could easily be called an overdeveloped resistance to the status quo. When I get into it with the religious right - or the political right - it’s usually because a character is challenging what I consider to be their ill-thought-out decrees. They call me blasphemous and I accuse them of putting their philosophy ahead of their humanity. On the rare occasions that I get into it with the politically correct Left, it’s because I use racial epithets in my writing or attach a personality trait to a character that seems cliché. Truth is, I can’t portray the kind of racist I grew up with without using racial slurs. If memory serves, I saw one African American person in the flesh before I was eighteen years old, but I heard the N-word every day of my life. So my writing is a reflection of what I know…or at least what I perceive. More simply put, I believe the controversy comes from the fact that one side thinks we can protect kids by keeping them from discovery, and I think we protect kids from helping then discover.

Q: Do you ever get tired of dealing with your books being challenged and having to justify their use in classrooms?

A: Not really because the truth is, I don’t spend a lot of time on it. I’ve responded so many times I know it by heart, so most times it’s just tweaking it a little for whatever the new censorship location is. It’s harder on teachers and librarians than it is me, and I’m always hugely grateful when they hang in there because they think there is merit to whichever story it is. I’m also aware that sometimes they just can’t do it.

Q: What makes you keep writing after all these years and all this controversy?

A: Well, the years of controversy don’t have anything to do with my writing. Every story is a new adventure for me…to see whether or not I can pull it off. Since I don’t think about the controversy while I’m writing, there’s no stress there, and when I’m finished writing, I have a little extra time on my hands. As you might imagine I’m one of those people who doesn’t mind a little controversy. When I match that irritation for lack of a better word, with the lives of some of the people I’ve worked with in therapy over the years, I can’t complain too much. Besides that, I always think I’m right.

Q: Who do you picture when you first start to write a book? Another way to see this would be, who is your audience? Has the audience for your books changed over the years? In what ways? Has your writing style or approach to book writing changed over the years? How? Why?

A: I’ve said this above, but I don’t think of audience. Like a lot of young adult writers I have a pretty wide audience. There are teenagers, of course, but I also get a lot of emails from adults. Other than the age of the protagonist there’s not a lot of difference between a good YA novel and an adult novel. The audience has changed some in that the YA field is pulling in a lot more adult readers these days.

Q: If you could be remembered for one YAL book, what would it be? Why?

A: Probably The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, or maybe a new one coming out called Muckers. Unfortunately I didn’t write either of those.

You’re asking me to pick a favorite child here, but to this point, probably Whale Talk. I have certain intimacies with many of the characters, it contains issues I’m passionate about and it’s probably as complex as anything I’ve written. Sarah Byrnes and Deadline are close seconds, though, and I couldn’t have had more fun writing the suspense/thriller aspects of Period 8. I have a certain love for all my books.

Q: What books spoke to you most when you were a teen? Why?

A: I only read one. To Kill a Mockingbird. How cliché can I get, huh?

Q: Teen readers relate strongly to your books, and many of them actually write you to express how much a book meant to them. Relate a favorite anecdote concerning one of those testimonies about the power of YA books.

A: One of my favorites came from a U.S. Army sergeant on active duty in Iraq. She’d had a rough go of it growing up and happened to read Whale Talk at just the right time. She kept a copy with her over there and at times gave it to certain other soldiers. Of course I made sure she got more copies. I think people don’t realize how our readers honor us - make our lives better than they ever had a right to be – simply by relating back how our stories happened to collide with their histories at just the right time.

The flip side of that was a girl who took me to serious task over a short story in which an Asperger’s syndrome character spewed racial epithets. She was a multi-racial kid who had probably heard some of those epithets hurled at her and she told me that, though she could take it, she didn’t want her little sister reading that crap. I received the email a few days before I was to do a presentation at her school, and I think she was goaded by some of her classmates into saying she wanted to give me the what-for one-on-one. Of course by the time I got there she had second thoughts; kids were taunting her and she was having to go face-to-face with the visiting author all the teachers had been talking about for weeks. She decided to bail, but I got the school librarian to bring her in with the promise that no bad would come of it. It gave me the chance to tell a kid that intellectual freedom includes the right not to read also, and that I thought she was really brave to stand up for what she thought was right and that she had a point. She hadn’t actually read the story because the language pissed her off in the beginning, so we went through it so I could explain my intentions. She couldn’t afford to change her position but was glad to accept a signed copy of the book and spent the bulk of our remaining time telling me what a rough life she and her sister had. It was all way more important than anything in the book.

Q: The books you're writing fit the same mold as books you've always written--how have you managed to avoid trends in YA literature that have made so many authors try different genres?

A: I’m kind of a one-trick pony. Most of those other writers have a greater capacity than I to try those different genres.

Q: Is there a certain type of teen you're trying to reach with your writing? The at-risk kid? The athlete? The disaffected?

A: It probably sounds smartass, but I’m trying to reach anyone who picks up one of my books. Writing about hard-time kids doesn’t only appeal to hard-time kids. Every kid, and in fact every adult, can relate to hard times.

Q: With so much dystopian literature being published recently, do you see a greater need for realistic fiction, stories that include teens our readers can more directly relate to?

A: I think any book that gets a kid moving his eyes left to right is a good book. I don’t care if a kid reads Goosebumps until he/she is thirty. If kids are engaged in the act of reading, then they have the tools to read whatever interests them at any given time. I think some of the dystopian literature seems as real as anything I write to some kids. I mean it sells like hotcakes. My stuff sells like oatmeal.

<<END>>

(PHOTO LEFT -- ALAN Keynote, Boston 2013)

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Q: Why does he write for young adults rather than any other age group? It would be interesting to hear about his writing process.

A: It wouldn’t be interesting to hear about my writing process; it’s diagnosable. It’s pretty much “what if…what if…what if…

I never think I’m writing for young adults. I think I’m writing about young adults. I like that aged character because that time is the first in our lives when we look at the world through what will become adult eyes. It’s an age that is often pooh-poohed by adults. We tend to call adolescent romance “puppy love” and consider teens problems frivolous, but how they handle those problems is the source material for how they’ll handle things as life gets more complicated. Brain science tells us this is a formative time.

Q: Chris, of all the touching characters you have given us, which one was hardest for you to write?

A: Probably Jennifer Lawless from Chinese Handcuffs. Though I had worked with a lot of girls with sexual abuse in their histories, I only knew it from the outside. I couldn’t afford to get it wrong because if I did, the entire book would be invalidated. Luckily two of the girls I was working with were voracious readers who wanted their stories told without actually having their stories told, so they became my editors. When I wrote something into Jennifer’s thoughts or conversation that didn’t ring true, they would let me know in no uncertain terms. Partly she was hard to write because she was so trapped. While I’m writing I’m paying so much attention to the craft that I don’t have much of an emotional response, but when I read it over later, I do.

Q: Do you ever hear the voices of potential censors as you write? Do you listen to what they have to say?

A: Naw, I don’t hear their voices as I write. I barely hear their voices when I’m in the room with them. Truth is, I don’t have much respect because the content of what they say is usually devoid of knowledge of child development or of how connection with characters spurs kids’ creativity. They consider themselves experts in education when most have never taken a class in education or tried to work with a classroom full of students. They project their own fear and discomfort onto students without ever asking students. Listening to their voices as I write would be like pouring superglue over my keyboard.

Q: Given our ever-shifting society, have your assumptions about your intended audience changed over the course of your career?

A: Not really. The “ever-shifting” is pretty much back and forth, so what goes around comes around. I don’t make a lot of assumptions about my intended audience anyway, and in fact don’t consider any one group “intended.” Every smart writer I’ve ever heard will tell you “The story is everything.” I’m more likely to write to one or two good readers who I trust to tell me when the story works and when it doesn’t.

Q: Which comes first as you envision a new story—the protagonist? The conflict? The outcome? Something else?

A: That really depends on the story. Sometimes an event will trigger a story and sometimes a person or persons will. I start with anything that fires me up; spurs my intensity. I would love it if the outcome got me started because I would know in which direction I’m writing from the first page, but that never happens.

Q: What is your most censored YAL book?

A: Whale Talk

Q: Any censorship battles that you lost? Or are still on-going?

A: God yes. Lost a bunch of them. The first one I lost I didn’t even know I was in… at Cascade High School in Cascade, Idaho, where I graduated. Students were required to bring a note from a parent to check out my first book. Nine hundred forty three people total in the town. My mother died three blocks from the house where she was born, so by the time it was published, she was the Grande Dame of Cascade, Idaho. If my mother walked into your house and you didn’t have a copy of Running Loose on your coffee table, woe be unto you. The only building in town where you couldn’t freely pick up a copy of Running Loose was the school.

Lost another battle to the Superintendent of Public Instruction of South Carolina, as near as I know the only Democrat who ever took me out. She was in a life and death political campaign for the U.S Senate against Jim DeMint (sp), that ultra-sensitive conservative SC senator who wanted all homosexual teachers and foster parents to be stripped of their certifications…and that was just the beginning for ol’ Jim. The State Superintendent (Inez Tenenbaum – who now works in the Obama administration) got hijacked by a small, loud group from the Christian Right who wanted Whale Talk and two other books – A Separate Peace and Lay That Trumpet in Our Hands – removed from a voluntary summer reading list. I think she decided she had to give them something, so Whale Talk became the sacrifice. She’d have been better off to go with A Separate Peace, given Knowles is dead. What she didn’t know was that coincidentally I had been invited to the South Carolina Teachers of English conference to deliver the keynote. Many of the members were so articulate in their anger that she took me up on my offer for a sit-down. She was far too ensconced on her position to back out, and we had a pretty uncomfortable discussion that started with me saying “I’ve had this argument a number of times in my life but never with a Democrat.” As far as I know the book still isn’t on that list. There are a number of others I’ve lost.

Q: Who do you write for? Yourself? Troubled teens? Both?

A: I really do write for anyone who might pick up one of my books.

Q: What do the censors find objectionable? The language? The context? Both?

A: It’s my belief it’s more context than language, though language is a more convenient target. I usually start out my part of the language argument saying I never read anything in the Christian Bible about “fuck.” But if I put a gay character in a book who isn’t a freeway sniper or a serial killer, I’m somehow putting gay ideas into kids’ heads that will surely turn into gay behavior. If a character defies authority there is often an accusation that I’m advocating that . Same with a character who has sex out of wedlock, etc. etc. Funny that they don’t complain too much about gunplay.

Q: You write novels that shed light on ‘dark subjects’ – kids do but often, do not tell – Do you think parents have a right to object because you are acting more like a therapist than a novelist?

A: This is the United States of America. Parents have a right to object to anything they want. I’m not sure if the questioner is saying I act more like a therapist than a novelist or if he/she ‘s saying parents think that, but shedding light on ‘dark subjects’ doesn’t mean I’m acting like a therapist. It means I’m taking knowledge I’ve acquired from being a therapist and using it to tell what I consider a truth about my characters’ lives. When it comes to rights, they have the right to complain and characterize me however they want, I have the right to write my stories, and readers have the right to read them. Those parents also have the right to forbid their kids to read my books, and I wish them luck with that, I really do. But they do not have the right to decide what other people’s kids can read and I’m always surprised at those times when they somehow get the right to tell educators how to educate. That is usually the fault of administrators who are more concerned with how the school looks to the community than serving their clients: the students and the teachers.

Q: As America becomes more diverse and inclusive, have you noticed a change in the censorship fights? More? Less? The same?

A: The censorship fights seem to be the same. As America becomes more diverse and inclusive, the censors become more threatened and therefore louder. I’m counting on this diverse population to finally make the censors’ arguments appear as ludicrous as they actually are. I do think this wonderful mix is going to change things. I’m tired of being embarrassed to be a white American male. I really wish I were going to live longer.

Q: Do you meet many arm-chair liberals? Parents who praise your work, but would rather have their kids read ‘Jane Eyre’ and ‘Great Expectations’ because that is what smart kids read?

A: I do, and I usually tell them I think it’s a mistake to do “either-or”. If you give any sharp YA literature expert a theme from any classic, he or she can give you that same theme in contemporary YA literature, and the theme doesn’t have to be explained so thoroughly because it’s in language today’s kids speak. If I struggle through a Shakespeare play, then have it explained to me, even by a great Shakespearian teacher, I miss the intimacy of connection with the character because rather than have the experience of connecting directly to that character while I’m into the story, I get it intellectually. So I may come away with an understanding, but I’m missing the passion of being buried in a good story in real time. There is value in that intellectual pursuit but if you want me to become a life-long reader you want to find a way to my heart as well as my brain. Plus, I can’t tell you the number of AP kids who have told me the best ways to make a teacher think you’ve read a story you haven’t read.

Q: Did you ever have someone get into your face? Directly accuse you of ‘damaging ‘ minds because of your dark and realistic writings..?

A: Yes. I’ve often been called “an agent of the Devil.” About a year ago someone came right out and called me “the Devil.” The actual guy. I thought, “I finally made it. I’m tired of playing second fiddle to that asshole.” So I had a beer. If I’m not being quite so much of a smartass I try to get them to imagine the thought processes I must go through to intentionally damage minds.

Q: Do you self-censor? If not, do you find yourself ‘doubting your choices?’

A: I wouldn’t call it “self censoring”. I don’t censor what I write about, other than I don’t write about things I don’t know about, or don’t feel competent finding out about. If I write something I feel is too graphic in the sense that it takes away from the story I’m trying to tell, I tone it down. What I don’t do is worry about what the so-called censors will think. That said, I am always doubting my choices. I live with the fear that some choice I make doesn’t push the story realistically where I want it to go. That’s one reason I love my editor. Even if we don’t agree we put words to the doubt and I have a better chance of making a right choice.

Q: Have your books become establishment? You are accepted because you are a name and therefore, if it is Crutcher, it must be good?...

A: Boy, if that’s true, I have no evidence of it. I think there are plenty of people who might say “this is a Chris Crutcher book,” or “this doesn’t seem like a Chris Crutcher book,” but I think in general if I write a book that’s not very good, I don’t get a pass.

Q: Working on something new that will raise eyebrows?

A: Am I ever. I’ve recently submitted a book about a character who shows up in a town twelve years after a horrific Christmas mall shooting. The kids who were visiting Santa Clause as first and second graders when it happened are now juniors an seniors in high school and the reverberations have ricocheted through all their school years. Gotta stop there, to avoid spoilers, but the conversations between Jesus and Superman in the main character’s essays alone could stir a little ire. (They’re really funny.)

Q: Chris: I have heard time and time again that if we don't have young adult readers read "the classics" they may never have cause to read them again in their lives. One might make the same argument for young adult literature.

A: One very well might, but in my mind that’s not the point. If you give me “the classics” and I have no emotional response to them, or they’re simply outside my capacity to appreciate, that’s a negative return. If I read a young adult novel that does get a passionate response from me, there’s a pretty good chance I’ll keep looking for stories that do that. Very likely they won’t be young adult literature down the road, but I will keep looking for the stories that draw me in. In other words, YA literature is part of a natural progression. There would be a lot better chance of my reading the “classics” in my later years had I been able to fall in love with stories I related to and then expand from there. We want to keep the idea of “development” in mind. Plus, the discussion about the classics and young adult literature isn’t “either-or.” They are in no way mutually exclusive. There are high school and even middle school students who will eat them up…love them. Those students should be encouraged to the max. They are the ones who will actually keep those classics alive.

Q: Is the introduction to young adult literature just as important as the introduction of classics in the secondary English classroom?

A: Yes.

Q: I think I'd like to know if he thinks his audience has changed much over the years. We always hear the statement, "Kids today..." followed by some big thing kids did or didn't do 20 years ago, but does he feel the teens he writes for now are very different from the teens he wrote for when he began writing?

A: Times change quickly. Evolution doesn’t. If the teenage Chris Crutcher weren’t far more like the teenagers of today than different, I wouldn’t be able to write about them. That “Back when I was a boy/girl” thing is a function of memory and perception. Things happen faster now. Information is more available. Competition for certain things has gotten ridiculous. But brain development and emotional/psychological development hasn’t changed.

Q: And, I'd love to know what other YA authors he enjoys as a reader.

A: Wow. On a given day probably a bunch of different answers. My problem answering is the number of far-better-writers-than-I that I would leave out.

Q: During your writing career, you've tackled many controversial topics and issues. Are there any topics that you avoid? If so, what are they? What makes you shun them?

A: There aren’t any I’d avoid that I know about. The only things that make me avoid a topic are ignorance or lack of interest.

Q: Why do your books seem to provoke so much controversy?

A: I think the biggest reason is a certain level of irreverence toward institutional thought. I have what could easily be called an overdeveloped resistance to the status quo. When I get into it with the religious right - or the political right - it’s usually because a character is challenging what I consider to be their ill-thought-out decrees. They call me blasphemous and I accuse them of putting their philosophy ahead of their humanity. On the rare occasions that I get into it with the politically correct Left, it’s because I use racial epithets in my writing or attach a personality trait to a character that seems cliché. Truth is, I can’t portray the kind of racist I grew up with without using racial slurs. If memory serves, I saw one African American person in the flesh before I was eighteen years old, but I heard the N-word every day of my life. So my writing is a reflection of what I know…or at least what I perceive. More simply put, I believe the controversy comes from the fact that one side thinks we can protect kids by keeping them from discovery, and I think we protect kids from helping then discover.

Q: Do you ever get tired of dealing with your books being challenged and having to justify their use in classrooms?

A: Not really because the truth is, I don’t spend a lot of time on it. I’ve responded so many times I know it by heart, so most times it’s just tweaking it a little for whatever the new censorship location is. It’s harder on teachers and librarians than it is me, and I’m always hugely grateful when they hang in there because they think there is merit to whichever story it is. I’m also aware that sometimes they just can’t do it.

Q: What makes you keep writing after all these years and all this controversy?

A: Well, the years of controversy don’t have anything to do with my writing. Every story is a new adventure for me…to see whether or not I can pull it off. Since I don’t think about the controversy while I’m writing, there’s no stress there, and when I’m finished writing, I have a little extra time on my hands. As you might imagine I’m one of those people who doesn’t mind a little controversy. When I match that irritation for lack of a better word, with the lives of some of the people I’ve worked with in therapy over the years, I can’t complain too much. Besides that, I always think I’m right.

Q: Who do you picture when you first start to write a book? Another way to see this would be, who is your audience? Has the audience for your books changed over the years? In what ways? Has your writing style or approach to book writing changed over the years? How? Why?

A: I’ve said this above, but I don’t think of audience. Like a lot of young adult writers I have a pretty wide audience. There are teenagers, of course, but I also get a lot of emails from adults. Other than the age of the protagonist there’s not a lot of difference between a good YA novel and an adult novel. The audience has changed some in that the YA field is pulling in a lot more adult readers these days.

Q: If you could be remembered for one YAL book, what would it be? Why?

A: Probably The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, or maybe a new one coming out called Muckers. Unfortunately I didn’t write either of those.

You’re asking me to pick a favorite child here, but to this point, probably Whale Talk. I have certain intimacies with many of the characters, it contains issues I’m passionate about and it’s probably as complex as anything I’ve written. Sarah Byrnes and Deadline are close seconds, though, and I couldn’t have had more fun writing the suspense/thriller aspects of Period 8. I have a certain love for all my books.

Q: What books spoke to you most when you were a teen? Why?

A: I only read one. To Kill a Mockingbird. How cliché can I get, huh?

Q: Teen readers relate strongly to your books, and many of them actually write you to express how much a book meant to them. Relate a favorite anecdote concerning one of those testimonies about the power of YA books.

A: One of my favorites came from a U.S. Army sergeant on active duty in Iraq. She’d had a rough go of it growing up and happened to read Whale Talk at just the right time. She kept a copy with her over there and at times gave it to certain other soldiers. Of course I made sure she got more copies. I think people don’t realize how our readers honor us - make our lives better than they ever had a right to be – simply by relating back how our stories happened to collide with their histories at just the right time.

The flip side of that was a girl who took me to serious task over a short story in which an Asperger’s syndrome character spewed racial epithets. She was a multi-racial kid who had probably heard some of those epithets hurled at her and she told me that, though she could take it, she didn’t want her little sister reading that crap. I received the email a few days before I was to do a presentation at her school, and I think she was goaded by some of her classmates into saying she wanted to give me the what-for one-on-one. Of course by the time I got there she had second thoughts; kids were taunting her and she was having to go face-to-face with the visiting author all the teachers had been talking about for weeks. She decided to bail, but I got the school librarian to bring her in with the promise that no bad would come of it. It gave me the chance to tell a kid that intellectual freedom includes the right not to read also, and that I thought she was really brave to stand up for what she thought was right and that she had a point. She hadn’t actually read the story because the language pissed her off in the beginning, so we went through it so I could explain my intentions. She couldn’t afford to change her position but was glad to accept a signed copy of the book and spent the bulk of our remaining time telling me what a rough life she and her sister had. It was all way more important than anything in the book.

Q: The books you're writing fit the same mold as books you've always written--how have you managed to avoid trends in YA literature that have made so many authors try different genres?

A: I’m kind of a one-trick pony. Most of those other writers have a greater capacity than I to try those different genres.

Q: Is there a certain type of teen you're trying to reach with your writing? The at-risk kid? The athlete? The disaffected?

A: It probably sounds smartass, but I’m trying to reach anyone who picks up one of my books. Writing about hard-time kids doesn’t only appeal to hard-time kids. Every kid, and in fact every adult, can relate to hard times.

Q: With so much dystopian literature being published recently, do you see a greater need for realistic fiction, stories that include teens our readers can more directly relate to?

A: I think any book that gets a kid moving his eyes left to right is a good book. I don’t care if a kid reads Goosebumps until he/she is thirty. If kids are engaged in the act of reading, then they have the tools to read whatever interests them at any given time. I think some of the dystopian literature seems as real as anything I write to some kids. I mean it sells like hotcakes. My stuff sells like oatmeal.

<<END>>

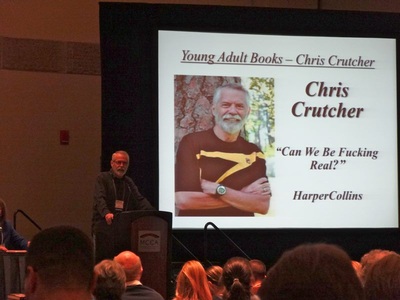

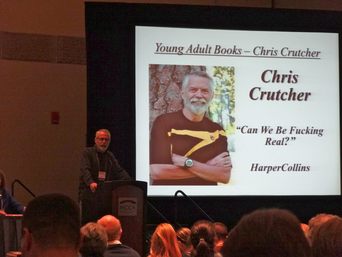

2013 NCTE/ALAN Schedule for CC:

Saturday, Nov 23

8:30 am -- 8 Great (Censored) American Novels

Sunday, Nov 24

8:30 am -- YA Authors, Censorship, and Good Advice

11:00 am -- Signing at HarperCollins, booth #1008

5:30 pm -- ALAN Cocktail Party

Monday, Nov 25

11:05 am -- ALAN Author Breakouts: ”Examining the Culture of Sports: 40 Years of Ball in YAL”

1:00 pm -- ALAN Chris Crutcher Keynote: “Can We Be F*****g Real?”

Saturday, Nov 23

8:30 am -- 8 Great (Censored) American Novels

Sunday, Nov 24

8:30 am -- YA Authors, Censorship, and Good Advice

11:00 am -- Signing at HarperCollins, booth #1008

5:30 pm -- ALAN Cocktail Party

Monday, Nov 25

11:05 am -- ALAN Author Breakouts: ”Examining the Culture of Sports: 40 Years of Ball in YAL”

1:00 pm -- ALAN Chris Crutcher Keynote: “Can We Be F*****g Real?”

- Home

- Contact

- Biography

- NCTE/ALAN 2013 Q&As

- Author Visits

-

Crutcher Books

- Other CC Books

- For Educators

- Angus -- The Movie

- Older News Briefs

- Photo Albums

- Scrapbook

- CC Videos

- Student Projects

- Censorship

- Banned Book Videos

- Teens CAN Stop Censors

- Banned Books Week

- Extras!

- CC Press

- Letters to CC

- Movie News

-

Crutcher Speeks

- Update Bantleman/Tjiong

- Nod to Gnuts

- Hip-Hop

- Good Day...

- Gun Referendum

- Free Neil and Ferdi >

- Responsi-damn-bility

- Whacking on Your Children >

- Piling On

- Biopsy Biography

- Walter Elevated Us All

- Different Direction

- Parenting Guidance

- Goodbye, Ned.

- Happy Birthday, Crutch!

- Forrest Bird Charter School

- Senator Portman

- My Gun Rant

- Maybe Now (Guns & Mental Health)

- Support Your Local Pragmatist

- So You Want to Be a Righter

- Philosophy and Humanity

- We Are Paterno

- Boy Scout "Leadership"

- Thoughts on McQueary

- To Meghan Cox Gurdon/WSJ

- India 2011

- Crutcher-Price Blog